An exploration of Maine’s maritime history

Published in The Weekly Packet | August 19, 2021

It took maritime historian, author, editor and curator Lincoln Paine 50 minutes to run through 200 years of Maine’s history during Castine Historical Society’s 12th Annual Deborah Pulliam Memorial Lecture on July 15 via Zoom. When his fast-paced lecture, titled “Perfected Visions of the Past: Maritime Maine in Almost 2020 Hindsight,” concluded, Lisa Lutts, the evening’s host and executive director of the historical society, said, “I’m going to have to watch this several times to grasp all that you were talking about, because there were a lot of new concepts in there for me.”

The full video will soon be available on the historical society’s website, castinehistoricalsociety.org. In the meantime, the public may explore the current exhibit, “Risky Business: Square-Rigged Ships and Salted Fish,” now through October 11. The subject matter is meant to overlap with Paine’s recent lecture.

Questions followed Paine’s lecture and discussion ensued. But, like Lutts, we could all use more time with such dense and insightful material. I chatted with Paine after the presentation to delve deeper.

Recognizing historical context

Paine began by briefly acknowledging elements of this extraordinary moment in history, saying, “tonight we’re celebrating Maine’s 200th anniversary as a state, but we are late due to the pandemic, and our country is embroiled in debates about our history and how we understand it.” He was quick to put it into historical context. “We have to remember that Maine’s statehood was nearly postponed because, in 1820, our country was also in crisis,” he said.

“Just because the media is awash with discussions about changes in historical frameworks doesn’t mean that historians are only now reevaluating how they think about things,” Paine continued. “Historians are always doing that.”

One of the topics that interests Paine the most is the segregation of history. We tend to separate and centralize European or Euro-American history, pulling it out of its context, (i.e., the rest of the world.) “I’m always interested in how to reintegrate views of history,” he told me over the phone, which is a theme in his latest book, The Sea and Civilization: A Maritime History of the World. “I really made a concerted effort to decentralize Europe and the West in telling the story of maritime enterprise, which is a global phenomenon,” he said.

According to Paine, the issue of narrow historical perspectives arises from human nature. “Common interests tend to be exclusionary,” he says. Bridge players talk about bridge, book clubs talk about books, that sort of thing.“We tend to write what we’re interested in,” Paine said. “I just happen to be interested in the really big mural.”

So when covering the evolution of the Maine Maritime Museum during his lecture – Paine serves on its board – he says it made sense that the institution has focused on shipbuilding throughout its history. After all, three of the seven original directors worked for shipbuilders, the other four came from shipbuilding families, and the 20-acre campus covers three 19th-century shipyards.

The museum has expanded its focus over time though, reflecting modern interests in art, economics, design, craftsmanship, work ethic, and traditional boat-building skills, since it used to house a shipwright apprentice shop.

“But,” Paine said, “we have to admit that our conception of worthwhile maritime traditions remains pretty narrow.” As an example, he uses the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor, part of the Smithsonian Institute. It focuses on Native American history, primarily of the Wabanaki Nations, and offers the only program he knows of that teaches basket weaving and provides either demonstrations or videos of birch bark canoe building, eel weir construction and spearing sturgeon by torchlight.

“Trying to incorporate and build bridges between predominantly Eurocentric or Euro-American oriented organizations like Maine Maritime Museum and the Abbe museum is, I think, very important,” Paine said during the question and answer period after his lecture. “Maine didn’t just sort of spring fully blown from the head of an empty North America, 200 years ago, or 400 years ago. There’ve been people here for a very, very long time.”

We see echoes of bark canoes in over a million Old Town Canoes sold and launched today, according to Paine’s lecture, and the basic design is modeled on the Native American original. “The canoe is also a staple of the state’s recreational economy,” he said. “So this all makes it a little difficult to understand the segregation of the history of Wabanaki watercraft, or the skills required to make them, from those of plank boats and ships. But I think we’re working towards harmonizing this a little bit.”

Romanticizing the past

Narrow tellings of history can also lead us to overly romanticize the past, according to Paine. Take the abandoned Hesper and Luther Little schooners, left in Wiscasset to rot. In the 1960s and 70s, thousands went to see them because they evoked a simpler, romantic era of wind-driven shipping.

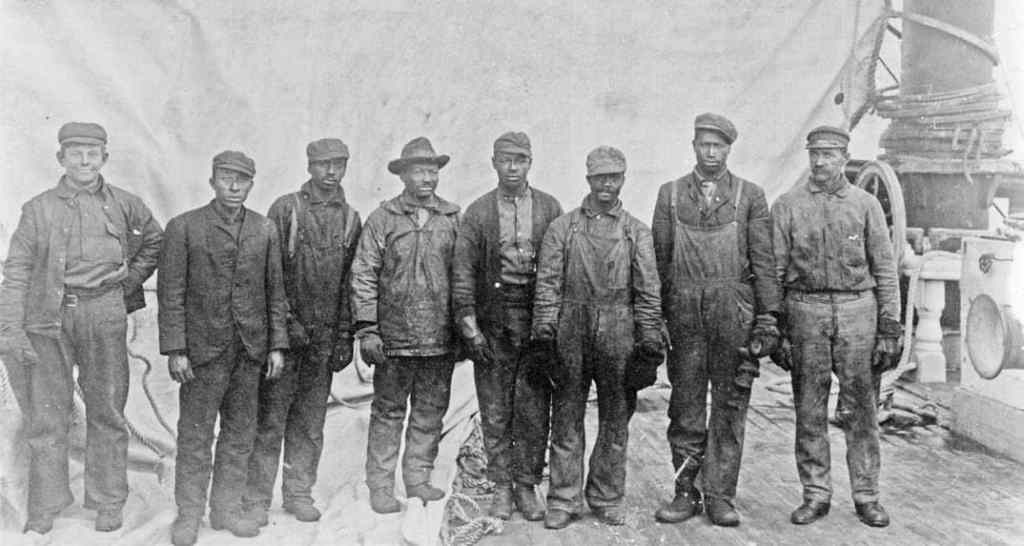

Paine doesn’t see old schooners in that light. “They were no more romantic than an oil tanker is today, and they were far more dangerous,” he said. Most shipped coal, linking them directly to the exploitative system in the coal mines of Appalachia. “Their crews were underpaid and overworked, as were most American sailors for most of our history,” he said. “There is no gain saying that these schooners were triumphs of the shipwright’s art, but it is a disservice to the memory of those that worked, and all too often drown in them, to paint a rosy picture.”

Of course, Paine covers Maine’s wartime history in the lecture — the British bombardment of Portland (then Falmouth) and the Americans’ failure to recapture Fort George in Castine during the Revolutionary war, Thomas Jefferson’s Embargo Act, smugglers, privateers, the lead up to the War of 1812, and the war itself. According to Paine, separation succeeded only after the war, as Maine was finally determined to protect itself and control its own natural resources instead of relying on Massachusetts to do so.

There was a catch though, Paine recounted. Congress was working to admit Missouri and Maine to the Union at the same time. “Sectarian politics in 1820 were far worse than they are today,” he said, explaining that the proslavery Speaker of the House, Henry Clay, fought against admitting Maine as a free state unless Missouri remained a slave state. That resulted in the Missouri Compromise, which allowed slavery to continue in Missouri.

The majority of Maine’s representatives opposed the compromise, but that didn’t change the outcome. “In fact,” Paine noted, “Maine merchants, shipbuilders, officers, and crew had been directly profiting from the slave economy ever since William Kind had entered the cotton trade between New Orleans and Liverpool at the turn of the century.” The importance of the trade only grew after the War of 1812.

“By 1860, 1.8 million enslaved people in the American South were producing upwards of a million tons of cotton a year, more than two-thirds of the world’s supply,” said Paine. About a quarter went to New England mills. Many of Maine’s ships delivered it. Others participated in the then legal interstate trade of enslaved people or the illegal international market. “From 1850 to 1865, there were more than 60 ships engaged in the slave trade that were either built, owned or registered in Maine, or captained by someone from Maine,” Paine recounted. Then came the Civil War.

Common interests unite

With this retrospective before us, Paine doesn’t see our country today as the most divided it’s ever been. “It’s pretty bad,” he told me in a phone call after the lecture, “but I think, probably, the period between 1820 and the Civil War, it was probably this bad most of the time, and then it got worse.” Then, he noted, in the 1960s, there were assassinations, riots, university lockdowns, and college shootings. “I think the problem is with this country that we’ve been here before. We’ve spent a lot of our time as a country very divided on critical issues about what the identity of our country should be,” he said.

And history doesn’t show him any easy paths to unite us. “Often crises bring us back together,” he said. “If you had asked me a year ago or two years ago if an event like a pandemic would have brought people together, I would have said, ‘Yeah, probably.’ But as we’ve seen, it’s been so horribly politicized that what might have been a moment of solidarity has been exploited to further divide people.”

According to Paine, finding interests that cut across society helps unite our stories today and in the future. Paine sees the environment as an example. “The environmental movement has been one that, for much of its history, did result from common interests and collaboration amongst groups at a grassroots level,” he told me on the phone. “You see a lot more collaboration at a grassroots level because people do tend to be collaborative and don’t necessarily want to segregate themselves.”

Of course, Maine’s history is the story of its ecology too. In his lecture, Paine shared that people had begun to worry about the sustainability of Maine’s fisheries even before the Civil War. “The first lobster conservation laws were passed in the 1870s,” he says. This isn’t a new problem. In fact, it goes back much further. Starting in the 1400s, overfishing in Europe pushed people to cross the Atlantic in search of cod, Paine explained. They eventually reached the Gulf of Maine. Then we industrialized.

In 1861, according to Paine, sailing vessels landed around 10,000 metric tons of cod within 20 miles of coastal Maine, an area of about 2,400 square miles. In 2007, they landed less than 4,000 tons from the entire gulf of Maine, an area 15 times larger. “The upshot is, that by 2015 cod were ecologically extinct,” he says. Now, climate change is forcing cod, haddock, and, eventually, lobster to migrate away to cooler waters.

“We live in a very rich, complex ecosystem,” Paine explained while responding to a question about aquaculture and fish farming in the discussion session after the lecture. “Now that we’re learning about how all these things are interconnected, we have to start actually doing stuff, to stop pretending like we’re just blindly wandering through life with no glasses on. Because, actually, we have the glasses, we just have to wear them.”

When asked to elaborate, Paine said, “I think, in the last year or so, more people are beginning to wake up to the fact that climate change is actually real,” he said. “Scientists and many policymakers understand what it is that needs to be done or should be done to mitigate the worst effects.” Too often though he sees people ignoring climate change or feigning helplessness. “Very often, the reasons people are saying there’s nothing they can do is because they kind of like things the way they are, because, in the short term, it benefits them,” he said.

When I asked him if he thought climate change would be the biggest story in the next 200 years, he responded, “Yep, definitely.”